My friend, lets call her MP (not a member of parliament and not scrounging for qualifications), is a very sarcastic and witty lass. She keeps on telling me that ‘Bodanomics’ is akin to ‘bad economics’ and that I am not far removed from a boda boda rider for the kind of thoughts I carry in my rather misshapen head.

I keep telling her I am okay with that. After all, boda boda riding has become a critical sector of our economy, and is now an established word in Wikipedia, the online dictionary. In any case, isn’t it true that the man who has a hammer, thinks of every problem as a nail?

The only economic tool of analysis I know that makes sense is incentives. I am such a sucker for the approach that I only make sense of things in the context of incentives. If I am wrong, that is okay, but that is my hammer.

My friend’s unflattering opinion of me is borne out of my equation of our decision-making processes to the choices of a boda boda rider. She is angry with me because the in my reasoning she too is a boda boda rider like me.

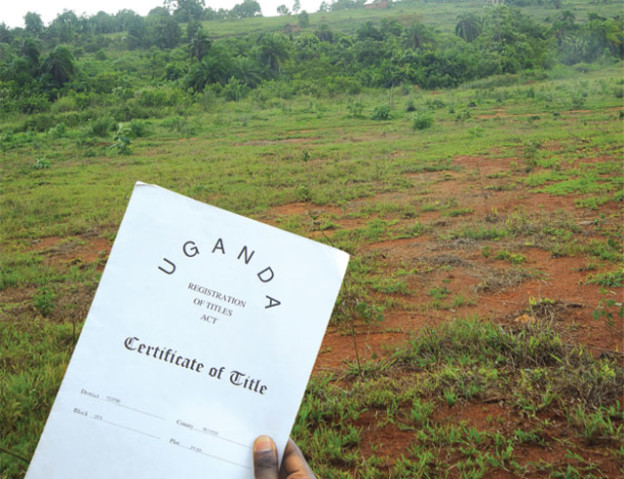

Take this argument we have been having over land. She argued that people should not be selling land; that it is very reckless to sell land. Instead of using it profitably, people are selling it to gamble and buy boda bodas (there she goes)! I agree with her on the fact that people should not be selling land permanently and willy-nilly because it is a finite commodity of strategic import. But that is as far as I am willing to go.

People sell land, I argue because they need money to carry out its three main uses: everyday transactions, speculation and precaution. If they can’t find money and have land, its their right to sell the land and live in the here and now. I have tried to explain to her that people sell land because they don’t have an alternative. The outright sale of land has gotten to a worrying point because all of us natives, rich or poor, have nothing else to sell.

We don’t want to spend the rest of our lives busting our backs while the lights are shining in the city. We are part of the here and now, so we have no incentives to preserve the land (as individuals) for tomorrow. That incentive should lie with the collective, which is represented by communities, tribes and government. But those institutions too probably have lost sight of that incentive because as the custodians of our common destiny, they are pursuing another set of incentives.

These institutions’ weakness has allowed us to live this dilemma. That weakness has allowed us to live in a situation where property rights relating to land are dissipated through an ambiguous multi-layered ownership and includes unfettered and timeless access to that sovereign right by foreigners.

While those entrusted with the common good are busy pursuing their own goals, we too are busy selling the family silverware and out competing the world in birth rates. Today Uganda has a birth rate of 3.2% with a population of 38 million people. That will be a cool 100 million by 2050 (see www.populationpyramid.net). Probably by then, bar legislative intervention, we will have sold off all the arable land (mark my emphasis). That is the prophesied city of Megiddo we are hurtling towards. Without recourse to other resources, and the attendant pressures what should we expect?

I am no prophet, but that is the situation we are facing if we don’t act with resolve as a nation. One needs to note that the next battles will be fought over megatrends like climate change and resource scarcity. With every passing day, our share of those resources grows (in relative terms) smaller and smaller.

Dr. Samuel Sejjaaka, is Country Team Leader of Abacus Business School. This and other articles can also be read at monitor.co.ug