As our first part concluded, the presenter opined that “ In Africa, the poor do not sleep because they’re hungry, and the rich do not sleep because the poor are awake”. If we were to move forward, we needed to a) re-instill fiscal discipline in the state which had become profligate, b) undertake second-generation reforms to re-align relations between the state and the market, and c) pursue a policy of industrialization to urgently reverse the ongoing premature de-industrialization.

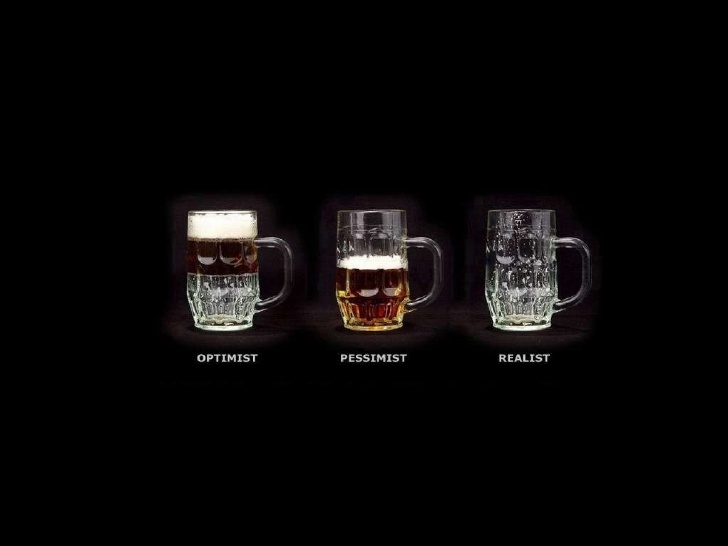

If you don’t understand what he was saying, let me explain. Fiscal discipline means living within our means. Realigning the state and markets means that our private sector is too small, it cannot deliver the growth we need. The state needs to participate in economic activity and boost markets. Industrialization means that in our growth trajectory, we cannot jump from being an agrarian society to a service society. We need industries to add value to what we produce and also create employment. From his point of view (economist), the glass was half empty.

Enter the second presenter, who was wearing a business hat. He seemed to suggest the glass was half full, and could only get fuller if we knew what the operating dynamics were. He observed that developing countries (like in East Africa) were generally the riskiest markets in which to invest. They had a high rate of population growth (and therefore dependency ratios), unreliable governments that were largely extractive rather than facilitative, and low capital formation.

Whereas these characteristics of frontier markets could be seen as limitations, they were reasons for optimism. First, high population growth meant more economic growth. As more people aspired to move into the middle class, they would consume more manufactured goods and were thus create a market for more products. Two, because developing country governments are fickle, the risk in frontier capital markets is not correlated to that in developed country capital markets. That means that while developed countries may be having problems, it does not follow that least developed countries will suffer the same set of problems. Thus if you want to reduce the risk in your investment portfolio, you can invest some of your money in frontier (developing) capital markets.

Again because frontier economies are growing faster than developed markets (even if risk is high), the potential for higher returns is greater. All this is evidenced by the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) frontier markets index. For 2017, the MSCI frontier market index had a return of 32.32% compared to a return of 24.62% for the all country world index (ACWI). Again in lay terms, what that means is that on average, for every dollar invested in a frontier capital market (developing country), the return was 32 cents!

However, there are some flies in the ointment. A few companies, especially banks, telecommunications companies and utilities, dominate developing country markets. Therefore there are hardly any shares to trade and the markets are not liquid. This is the headache for fund managers in developed countries where returns are so low, you almost have to pay for someone to borrow your money! Enter the equity fund. If you are not watching, Equity Fund managers have hit the scene, looking to buy up a share of well-managed businesses and invest even more.

Thus when you look at the glass from the new comers’ (Equity Fund Managers) point of view, they are saying developing countries are unexploited markets. They are hungry for capital and they have a rapidly growing population that aspires to the good things. On the other hand, developed markets have declining populations, are over invested and returns are low. So why not invest some money (that we don’t mind losing) in these developing country markets?

If this does not make much sense, don’t worry. Just lie back and wait for Mr. Jones to come and fix your workplace. This is the new post neo liberal dispensation.

Samuel Sejjaaka is Country Team Leader at Abacus Business School @samuelsejjaaka