Academics (especially economists) are accused of being indecisive. They will talk of ‘many hands’ or assumptions and leave you with no clear answer. I find myself in that exact position after last week’s very short history of taxation. The argument I was presenting then was to the effect that hadn’t humans experienced an agricultural revolution and learned to live in settlements, the concept of taxation would never have arisen. Once human beings developed permanent civilizations, taxation of the surplus became inevitable for purposes of providing public goods and services. The problem was and is always with the allocation of the tax revenue and the definition of public goods. Up to today, these are not settled questions and hence my dilemma.

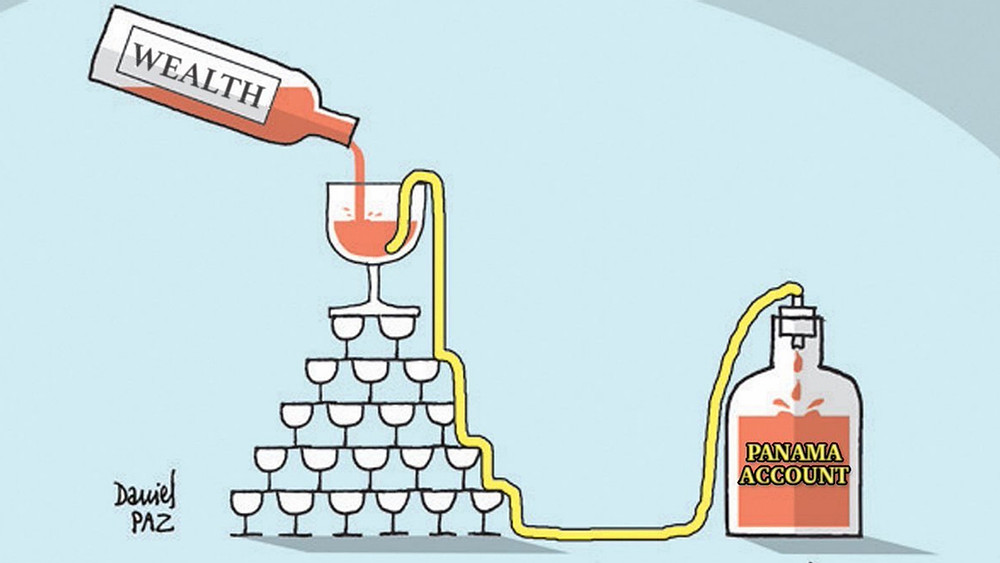

Over time, different civilizations tinkered with systems of taxation (which is a necessary evil) and how to apply them to manage their societies. Some argue(d) for more taxation while others have argued for less taxation. Those who argue for less taxation have been labeled supply side economists or trickle-down theorists. Trickle-down economics ( theory) is the proposition that taxes on businesses and the wealthy in society should be reduced as a means to stimulate business investment in the short term and benefit society at large in the long term. The term became very popular under Reagan’s presidency with massive tax cuts for the wealthy being implemented. It became popularized as part of Reaganomics. Under the Trump era, there were several attempts at the revival of trickle-down economics.

Unfortunately, the evidence shows that the proposition has never managed to achieve its stated goals. Several studies suggest a link between trickle-down economics and reduced growth. A lot of data has been analyzed and it is generally agreed that trickle-down economics does not promote jobs or growth, and that “policy makers shouldn’t worry that raising taxes on the rich harms the economy. Critics refer to trickle-down economics as ‘pissing on the poor’.

Enter the behavioral economists with their ‘nudge theory’. According to this theory, a nudge is a method or way of increasing positive reinforcement (good behavior or actions) through indirect suggestions as a way of influencing the behavior and decision making of groups or individuals. When an individual’s attention is drawn towards a particular option, that option will become more salient to the individual, and he or she will be more likely to choose that option. The sum total of their thesis is that when people see rewarding behavior in others, they are likely to follow suit. A typical local case is the farming campaigns you see in the mainstream media regarding ‘successful’ farmers. This is part of not understanding the problems of the poor.

A major criticism of nudge theory is that it is trickle-down economics disguised as another flavour of the season fad. Such fads, which are not based on good evidence, do not help people make long-term behaviour changes.

So what are to make of all this? One is that effective governments intervene by developing and financing programs that change peoples’ lives directly rather than by creating abstract incentives that only benefit those who are already advantaged like the wealthy and educated. That is why the Americans are trying to pass a USD 2 trillion infrastructure plan to achieve a multitude of objectives. The second point is that in order to provide ‘public goods’ governments must raise revenues and the most obvious way to do that is through taxes – which takes us back to how those taxes are used to provide public goods, or how those public goods are defined. Third and probably most important, is that you cannot achieve growth or development amidst a sea of poverty. Governments must legislate and intervene to change the fortunes of the masses in order for there to be prosperity.

As some sages have noted, the world is full of zombie ideas that have survived in public policy discourse despite being ineffective in achieving their intended consequences. Trickle-down economics and nudge theory illustrate that point very well.

Samuel Sejjaaka is Country Team Leader at Mat Abacus Business School. Twitter @samuelsejjaaka