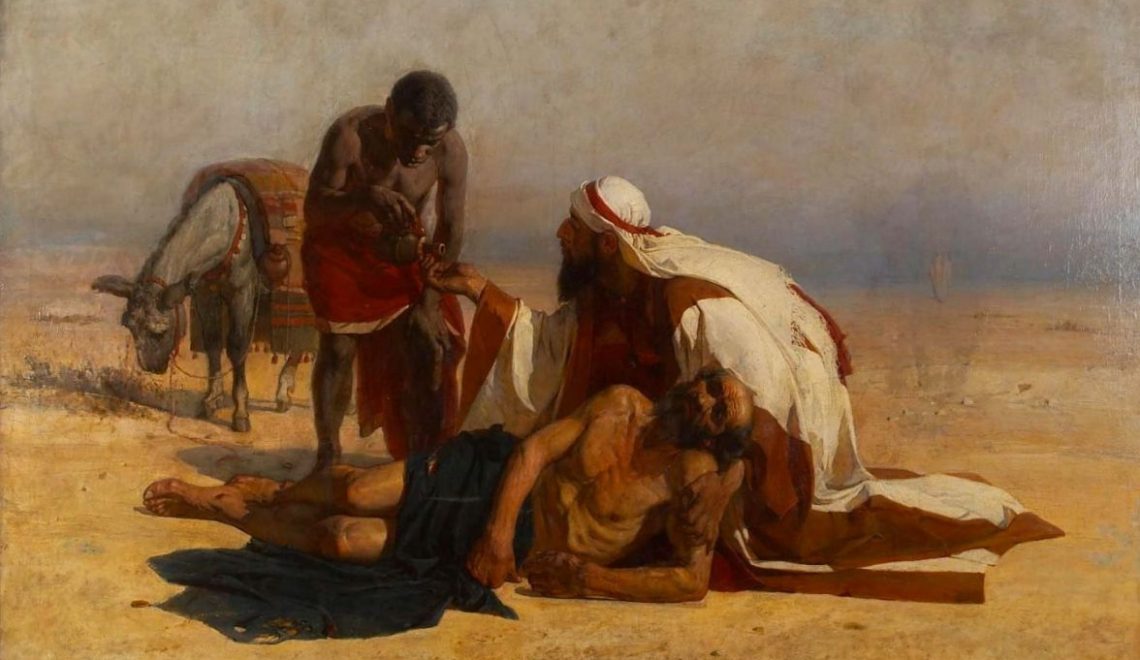

We have all probably heard of the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan’. It is supposedly a story of compassion, and kindness. The parable of the ‘Good Samaritan’ is found in the Gospel of Luke. Jesus tells the story of a traveller who is ambushed, beaten, stripped of clothing and left for dead by the roadside. First a Priest and then a Levite come by, but both avoid the man. Finally, a Samaritan chances upon the unfortunate traveller and helps him.

The story is important because Samaritans and Jews despised each other, but the Samaritan helps the injured man (a Jew). Jesus told this parable in response to the question from a lawyer, “And who is my neighbor?” The import is that your neighbor is the person who is willing to come to your help in your hour of need.

The parable of ‘the Good Samaritan’ was wormed its way from theology into many fields that impact our lives daily. For lawyers there is what is now called ‘Good Samaritan’ laws. These laws offer legal protection to people who give reasonable assistance to those who are, or who they believe to be, injured, ill, in peril, or otherwise incapacitated. The protection is intended to reduce bystanders’ hesitation to assist, for fear of being sued or prosecuted for unintentional injury or wrongful death.

For ethicists, the parable has entered into the field as a paradox: a situation in which one has to make a decision based on two moral imperatives, none of which can be said to be right or wrong. The paradox becomes a dilemma because obeying one moral imperative leads to breaking another.

From Ethics, the parable of the ‘Good Samaritan has wormed its way into economics. Economists argue that the Samaritan’s behavior was an act of charity. Because economists are (always) obsessed by incentives, they argue that giving charity leads to two outcomes, one of which may be desirable, and the other counter productive. The desirable one is that those who receive charity will use it to improve their situation. The alternative is that they will come to see charity as a solution to their problems and thus become less enterprising. The more aid that is received the less likely it is that the recipient will seek out a permanent solution for their condition.

Economists have argued this point to death so you probably don’t have to beat your brains out. They have also conducted experiments (and continue to do so) that show that aid is in the long run counter productive. Their biggest social experiment has been Africa. Ever since the Europeans gave us independence and weaned us from exploitation, they have been giving us ‘aid’ in return. For all their aid, there is not much proportional good to show because the biggest aid recipients are still the most needy. They have become slothful and spawned an industry in which European taxpayers and donors are conned of millions of dollars every year to feed the aid crowds’ jet set lifestyle.

Which brings me to our President’s cash handouts. The President seems to have opened a Pandora’s box by dishing cash handouts to different groups, noble intentions not withstanding. As with the case of the ‘Good Samaritan’ the cash handouts have probably helped some to improve their condition while others have merely enjoyed the windfall. If the latter is the most prevalent outcome, then the recipients must be working on the next scheme for another handout. And once they are addicted, they will come to expect and demand to receive these handouts which encourages slothfulness. For those who are not lucky the first time, they will organize and act as offended because they believe they are more deserving.

The point is that there is no end to what our own ‘Samaritan’ will be expected to give. That is until those who pay taxes demand that the President stops being a ‘Chuck Norris’ of sorts.

Samuel Sejjaaka is Country Team Leader at Abacus Business School. Twitter @samuelsejjaaka