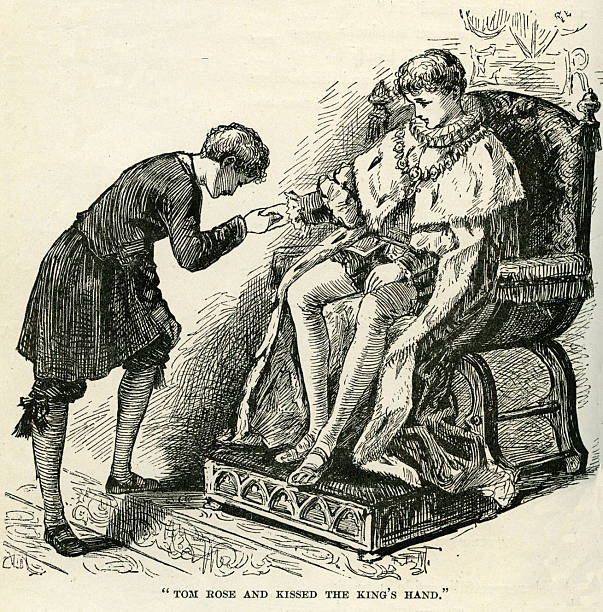

Mark Twain wrote the original tale, ‘The Prince and the Pauper’. It was about two characters, one a prince, and the other a pauper. In Twain’s fictional tale, he narrates the story of two young boys who are identical in appearance: Tom Canty, a pauper who lives with his abusive father and Prince Edward, son of King Henry VIII. The two boys get to know one another. Fascinated by each other’s life and their uncanny resemblance to each other (including being born on the same day), they decide to switch places “temporarily.”

As Edward experiences the brutal life of a London pauper firsthand, he becomes aware of the stark class inequality in England. In particular, he sees the harsh, punitive nature of the English judicial system where people are burned at the stake, pilloried, and flogged. He realizes that the accused are convicted on flimsy evidence and human branding – or hanged – for petty offenses, and vows to reign with mercy when he regains his rightful place.

Edward eventually regains his privileged position and is crowned King. Of course this is a fictional tale but it instructively reminds us of the mental gulf between the ‘princes’ who have the privilege to make fateful decisions over the lives of ‘paupers’, never having experienced the difficulty of being a ‘pauper’. It is also a brutal reflection of how the world really works. A kind of inverted ‘market for lemons’ I would call this problem. One in which there is a deficiency of effective public quality assurance and regulation of the actions of the ‘princes’.

Now imagine a policy maker ‘prince’ who has spent most of his working life in an air-conditioned office. He enjoys the use of a government car, travels first or business class and partakes of the choicest viands at the choicest eating-places courtesy of the taxpayer (pauper) of course. It is this same prince who has a prepaid phone and does not know the price of fuel, but is charged with the important role of making policy for governing the ‘paupers’. Having no experience of how paupers live, the prince is most likely to think of them as spendthrift, lazy and willful tax dodgers who should be hanged at the stake.

Like the Queen in ‘Alice in Wonderland’, on seeing ‘paupers’ (replace this with trader, businessman or peasant if you wish) his rallying cry will be ‘off with his head’. Is it any wonder then that the ‘prince’ spends his time laying schemes to tax the ‘pauper’ to death? Even when it is obvious that the ‘pauper’ is the one who lays the golden egg? It thus came as no surprise this week to learn that mobile money transfers had fallen by as much as Ugx. 600 billion since a tax was imposed (sic). This, despite all the noises made about its unprincipled nature and the actual (versus the ‘princes’ imagined) state of the economy. All you will hear the ‘princes’ shout is ‘Ugandans don’t like to pay taxes’. This, without any empirical evidence and ironically when the ‘princes’ probably pay the least taxes pro rata.

How then can we make the ‘princes’ understand the capricious nature of some of their decisions? How about if the prince and the pauper switched places? How about if they let some ‘paupers’ run their air-conditioned offices (temporarily of course) while they came down to ‘Kikuubo’ to run the small businesses of the paupers? Even if it were for a week, we would all get to learn about the immense ‘knowledge’ and ‘experience’ of the ‘princes’ in managing everything.

Maybe the princes would get to see the harsh and punitive injustices occasioned by some of the policies they impose on the ‘pauper’ class without having lived the latters’ experience. I doubt that this could ever happen as an experiment. But take heart, it usually does happen when a mighty ‘prince’ falls out of favor. Nature has a way of leveling some of these things.

Samuel Sejjaaka is Country Team Leader at Abacus Business School. Twitter @samuelsejjaaka