If economics were a being, he/she would be a hydra ‘handed’ monster. It has a way it plays tricks on men and women, great and small. It dares to tease and fool at the same time. It will show up the ‘exuberance’ of those who act on its ‘principles as well as their ‘irrationality’ in a symphony no one could ever dream up.

It was therefore more than bemusing to see Kibaale’s peasants receiving land titles from the powers that be. In the heat of the moment, and without the benefit of hindsight, that must have been a joyous event for the recipients. In the long run, that fellow called economics may deal another ‘invisible hand’ based on the law of unintended consequences which populism often tends to ignore.

Perhaps I am getting ahead of myself. Let me go about this in a more logical manner. When the Mengo administration devised “Kyapa mu ngalo” it was the indefatigable Minister Amongin who stood up to warn of the dire consequences of this exercise. It was illegal, evil and all the vile things she could think of. Despite Mengo’s plaintive appeal that “Kyapa mu ngalo” was intended to enfranchise bibanja holders who wished to be titled, the Minister was having none of it. Many joined in the raven’s chorus (even as they stole to Mengo to have their own bibanja titled). For now, the fellows on the Kabaka’s hill seem to have ducked low.

So you can imagine my surprise on seeing the lady minister grinning, as the President handed out titles to the peasants of Kibaale. No doubt the intentions are noble but as I told you earlier, this fellow economics is a cruel handed monster that flatters to deceive.

A little recent history of the economics of redistribution will illustrate the point. When Margaret Thatcher ascended to the office of British Prime Minister circa 1979, she pushed through a policy to sell off public assets, including council housing and government companies. Council houses were sold to sitting tenants while shares of public enterprises were enticingly offered to the public, especially the natives.

In the short run everyone was happy, as there was a perceived redistribution of wealth and everyone would live happily ever after. However within a period of five years, most of the shares sold to the public had been resold to institutional investors to pay for perceived wants of the commoners. What had been held in trust for the British public was now the sole preserve of private capitalists. Many also lost their homes to shrewd investors.

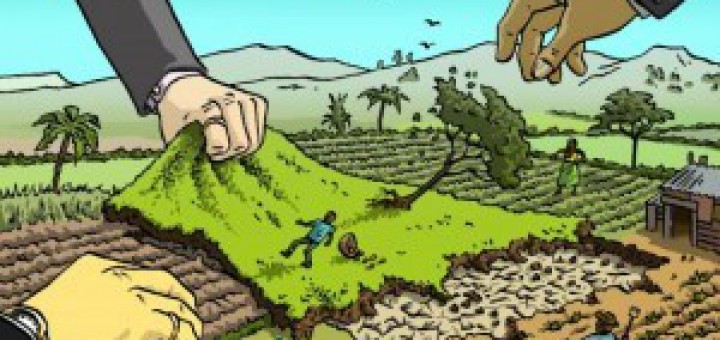

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions. In acquiring titles, the peasants of Kibaale, have become landowners and that, all factors held constant, is better than being squatters. But these land titles also provide for the means by which they can be legally removed (bought) from the land.

In the perverse sense of economics then, they have just drunk from a poisoned chalice. The truth is that the fundamental reason for being peasants has not been addressed. They will remain peasants because they do not have skills to propel them into the twenty first century. Since they too have aspirations, the land titles as a means of exchange, will provide an opportunity to offer their offspring a better education.

If land is commoditized, then it becomes freely tradeable and the communal veil that once protected the peasants is lifted. Recall that we have been here before. Civil servants who acquired public property in Nakasero, Kololo and Bugolobi (with good intentions again) have since been replaced by a new bourgeoisie. Kibaale’s land redistributions may be driven by good intentions but may end up with the perverse unanticipated effects of legislation and regulation. As Robert Merton warned, we must always beware “the imperious immediacy of (self) interest”. I sincerely hope mine is a self-defeating prediction.

Samuel Sejjaaka is Country Team Leader at Abacus Business School. @samuelsejjaaka