Introduction

Over the last six months the shilling has been losing its value. That is normal one would say. For since the currency reforms of 1987/88 when the shilling was pegged at Ugx 60 to the US Dollar its been a one way ticket (see chart for last 10 years). However, over the last six months the shilling has lost its value by as much as 28% (June 2015) and despite some revival occasioned by Bank of Uganda’s intervention, the slide has continued inexorably. We need to be concerned and respond accordingly to protect the inherent store of value that our currency ought to be. In order to do that we need to understand why the shilling is on the road southwards. Here is an economics 101 lesson on why and what we should be doing. I have identified six reasons (pressures) for the shillings woes. Some of these pressures are interconnected and self-reinforcing.

Low Productivity

Uganda suffers from incredibly low level of productivity per capita and this cuts across both the private and public sectors. In 1962, Uganda exported about 2.2million bags of coffee. The population was about 7 million. In 2014 Uganda exported about 3.6m bags of coffee. The population was 38 million! (see table 1 below).

Table 1: Per Capita Productivity for Coffee and Cotton

|

Year |

Pop (m) |

Coffee |

Cotton |

|

‘000s |

‘000s |

||

|

(60 kg bags) |

(480 *lb bales) |

||

|

1962 |

7.24 |

2,190 |

200 |

|

18 kg per capita |

13.26 lb per capita |

||

|

2014 |

38 |

3,600 |

100 |

|

6 kg per capita |

1.26 lb per capita |

Source: Index Mundi *(lb = pounds)

Studies across the region and the world have shown that this poor productivity is largely responsible for the high cost of doing business and inability to compete globally. According to the World Bank Group’s Ease of Doing Business Index, Uganda comes a paltry 150th out of 189 countries, beating only Burundi in the region

Low productivity is complicated by low value addition. As in the 1940’s Uganda is still exporting the bulk of its traditional cash crops as raw materials. Not only is it exporting unprocessed cash crops, but the relative increase in output of these cash crops has also been declining per capita. On the hand, due to an increasing population (growth rate of 3.2% to 3.6%) imports have been increasing, creating enormous balance of payments pressures and a veritable trade deficit.

Table II: Ease of Doing Business In Uganda, 2014/2015

| TOPICS |

DB 2015 Rank |

DB 2014 Rank |

Change in Rank |

| Starting a Business |

166 |

162 |

-4 |

| Dealing with Construction Permits |

163 |

162 |

-1 |

| Getting Electricity |

184 |

181 |

-3 |

| Registering Property |

125 |

120 |

-5 |

| Getting Credit |

131 |

125 |

-6 |

| Protecting Minority Investors |

110 |

108 |

-2 |

| Paying Taxes |

104 |

101 |

-3 |

| Trading Across Borders |

161 |

163 |

2 |

| Enforcing Contracts |

80 |

79 |

-1 |

| Resolving Insolvency |

98 |

126 |

28 |

Source: World Bank Group (based on 189 countries)

Global Economic Pressures

Since the global melt down from the American mortgage crisis of 2008, most of the World has been reeling from the after effects. Some like Iceland caught the first wave effects. Countries like Uganda and other sub Saharan neighbours were caught in a tertiary wave of reduced development aid and falling access to credit as many European economies shored up their treasuries to lick their wounds from America’s borrowing binge.

Surprisingly the American economy has rebounded but Europe sunk into crisis. This crisis has made the US dollar the currency of choice, leading to massive transfers of investments into American dollars. The Euro’s crisis has in other words been the Dollar’s gain. Add to that a general slow down in China and falling commodity prices, especially oil, and you begin to see why our shilling is taking such a knock. Lost jobs and incomes in the diaspora mean reduced FDI’s and remittances.

Fiscal and Monetary Pressures

Uganda’s economy is facing an ever-increasing public sector borrowing requirement (psbr) as the government attempts to support a burgeoning public administration and increasing demand for social services. In order to meet it budget deficit, the government has resorted to the sale of financial instruments in both the short and medium term, thereby increasing treasury bill and bond rates. T-bill auctions for July 2015 across all tenors were 14.1% (91 days), 15.9% (182 days) and 17% (1 year) while the interbank rate touched 27%. This has had the effect of crowding out private sector credit, and further reducing access to investible funds.

The ‘Akol’ syndrome is a reference to the changes that have taken place at the Uganda Revenue Authority. Since the arrival of Doris Akol in the corner office at Uganda Revenue Authority, tax collections targets have been overshot. The ‘Akol’ syndrome, means that a more efficient URA, increases the rate at which liquidity is transferred to from the private to the public sector. While this is good news, it reinforces the allocative inefficiencies that are typical of the public sector, again depriving the private sector of much needed investible funds.

To shore up the shilling, the Bank of Uganda has been increasing its central bank rate (CBR) in a bid to dampen volatility. It has also been deliberately selling off dollars to dampen demand. The assumption is that higher interest rates make the shilling more attractive and would encourage international investors to sell dollars to buy shilling investments (t-bills and bonds). These measures are effective in the short term but controversial because they destroy businesses by starving them of credit and worsening their interest to income ratios (ITI). Not only do non-performing assets increase, but jobs are also lost in the long term. ‘Injecting “a few dollars more” is akin to an old man peeing in the sea”, according to one scholar. “You are treating a symptom, but the cause is systemic. You ought to have a long term view of the solution and invest strategically to rebalance the economy.” As I write this, the CBR is at 16%, having shifted about 450 basis points in the last four months. Which country does that kind of thing, without the citizens objecting?

Political Pressures

When it’s election time, the first victim is fiscal discipline. Just like we saw in the 2011 election cycle, the electioneering has reached fever pitch, worsened by a major fall out in the ruling NRM. The purging of John Patrick Amama Mbabazi has not been without consequences. It has meant increased security and administrative budget allocations to stave of the ‘challenger’ and prevent him obtaining a foothold in any of the party’s extensive structures countrywide. Add the creation of new counties and municipalities, and you begin to redefine the term ‘gerrymandering’. All in the name of democracy.

The NRM may have won that battle, but what has it done for the economy? Sending jitters amongst investors, many have adopted a ‘wait and see attitude’. So there won’t be much happening until this phase is over and resolved. This has also noticeably impacted FDI’s while spurring a capital flight of sorts, as many well to do people keep something away for the proverbial rainy day.

Structural Pressures

This is the debate that will not go away. In liberalization and privatization of the economy, we have handed the ‘commanding heights’ to multinationals and foreign investors. The structure of our economy today is such that most businesses are foreign owned and run. The periodic externalization of profits in the form of dividends exerts a tremendous pressure on the shilling at this time of the year. Coming in the light of other on going pressures, 2015 seems to have been a tad harder on the poor shilling. But liberalization is the path we chose and it is not necessarily a bad thing. Its just that we arrogated the responsibility of looking out for ourselves to MNCs. The consequences we must live with.

Governments have a tendency to want to do everything and all things around election time. Without steady and ongoing infrastructure investment programs, it suddenly becomes urgent to do up all the roads, fix the dams and get the trains on to a better standard gauge rail! Suddenly the investment in these so called ‘non-tradable’ increases the pressure for externalizing hard currencies to the countries of the contractors. Dams and rails are not a bad thing, but they don’t create dollars in the short term because they are non-exportable services (therefore non-tradable) and have a gestation period whereby they add no value to the local currency.

But the wheeling and dealing in huge government contracts also carries a ‘rent’ otherwise known as the gravy train or in queens English – corruption. The back and forth haggling that goes with the award of these projects means that the local Mr. ‘Fifteen Percents’ must have their pound of flesh. That’s how things work and we must pay a little more than we ought to pay in a free market. Only that the commission agents also need dollars!

Geopolitical Pressures

It never rains but it pours. While we have been having our share of misfortunes, our hinterland (read strategic markets) have been beset by their own political problems. War in the Eastern DRC and South Sudan have significantly affected trade, thereby starving Uganda of the badly needed dollars collected form those markets from food and fast moving good (re)exports. South Sudan especially has been a big loss, given the fact that it had good income streams from oil, even if those oil prices were themselves falling.

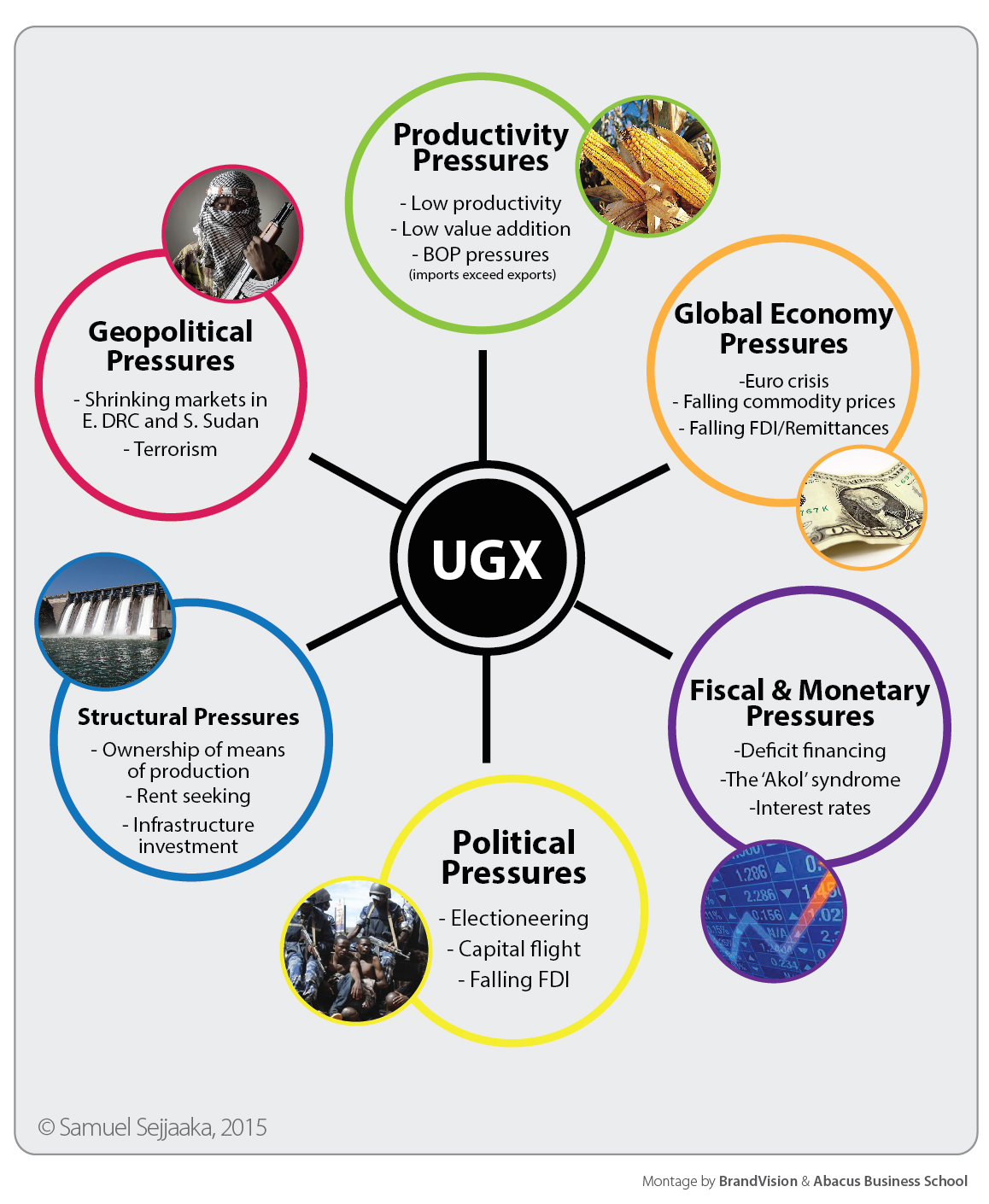

Add the impact of Al Shabab and other terror groups in the region and you have your tourists voting with their feet. This increases the spend on security, while providing negative publicity (and travel advisories in foreign countries) to what would otherwise have been an idyllic getaway. The loss of these tourists means loss of hard currency inflows. The pressures are captured in the montage below.

Which Way Uganda?

There are no quick fixes. Most of the issues we have to contend with have been long in the making. Failure to effectively implement government programs such as the plan for modernization of agriculture, export promotion, water for production (irrigation), grain storage infrastructure and low value addition are a result of a poor sense of purpose on our part. Our attitudes to ‘lifting our people out of poverty’ have really been lack lustre at best. The institutional lethargy that has created this state of affairs has belly flopped the economy.

There are things that we can do in the short term and there are things we must begin to do for posterity, otherwise we will not have much to count for all these years of relative political stability. We all agree that Bank of Uganda (on the admission of its CEO) cannot stave off the shillings’ depreciation. But they can manage the volatility to create some sense of certainty in business planning

We must move to immediately bring the cost of doing business down. It is inconceivable that the ‘one stop’ investment centre has never materialized. Why can’t we fix such ‘small things’ about which we have no disagreements? Does anyone disagree that we must improve productivity. Improving productivity is a process that starts by ensuring there are stable farm gate prices and more wholesome local value addition. Therefore we must create a network for incentivizing farmers to produce more and also ensuring that there are storage systems to mop up the bumper harvests. Simply encouraging farmers to produce more wont do on its own.

The cost of public administration must be dealt with. The argument that we are taking services nearer to the people sounds stale and tired! A burgeoning public administration just crowds out investment in the productive sectors of the economy. This huge public administration is also partly responsible for the inflationary spikes that we are witnessing. Year on Year inflation is now at 5.9%.

Some structural pressures can be managed with the right policy mix. Unless some of the inputs in large infrastructure projects are not locally available, there is no benefit for the economy in externalizing hard currency for what we can ably produce (cement and steel). This is akin to exporting our jobs to China! Pro local industry policies to buy Ugandan must be supported, as part of an import substitution drive and also to save the jobs they engender.

Conclusion

The means for our economic emancipation are within our hands and grasp. We know the problems and we know the solutions. It is inconceivable that we chose to be slovenly and uncaring, deciding to live off loans and grants. How will posterity judge our generation(s)? We cannot bequeath such a debt burden to our children and their children in perpetuity. Do we not have an iota of shame? It’s taken time for us to get to such a pass. It will equally take a measured effort and time to get ourselves out of this predicament where we can’t sustain our appetites for what we cannot produce.