Psychologist Walter Mischel died last year. If you didn’t know him you still may have heard of his ‘infamous’ marshmallow experiments. In these experiments, Walter Mischel and colleagues designed “the marshmallow test” in which a child was asked to choose between a larger treat, such as two cookies or marshmallows, and a smaller treat, such as one cookie or marshmallow. After stating their preference (usually the larger treat), the child was told that in order to obtain that preference, it was necessary to wait for the experimenter to return. The child was also told that if he or she signaled to the experimenter before they returned, the experimenter would return and the child would receive the smaller treat. To get the larger treat, the child was required to resist the temptation to get the immediate gratification assured by the smaller treat.

The marshmallow tests demonstrated the importance and ability to delay gratification and also helped in identifying strategies that make it possible to delay gratification. According to these experiments, children who were best able to wait in that situation when they were four years old were probably going to be more socially and academically successful as high-school students and generally performed better in aptitude tests. When Mischel followed up with the parents of the children who took the test years later, he found a staggering correlation between those kids who had difficulty delaying gratification and their outcomes in life as adults. Mischel’s experiments have since been criticized for pegging a lifetime of experiences to a 4-6 year old’s reaction to the offer of either one or two marshmallows. Whatever the veracity of his findings, the message for us is clear.

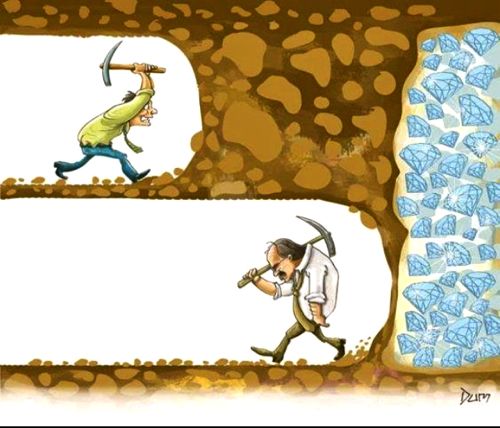

Forbearance is as important in early life as in adulthood. It is as important for countries as it is important for children and adults. Unfortunately in this age, forbearance is the road least travelled – with many of us individuals and countries failing to make wise choices, and choosing to live in the moment. In economics, an alternative way of looking at immediate self-gratification would be in terms of opportunity cost. The benefit foregone by consuming now what could have been consumed tomorrow or taking ones irons out of the fire too quickly.

Our generations have largely forgotten the idea of forbearance. They have also been sold the assiduous lie that Africans did not or do not save. This is a complete untruth. I clearly recall my grandmother’s uncanny ability to distinguish between ‘food’ and seeds. Granaries (ebyaagi) were a common feature in serious households. How then can we talk of the ‘lack of a savings culture’? Until the advent of biotechnology companies and genetically modified foods, forbearance was what ensured that our people did not go hungry. Slowly and inexorably, our people are losing the fight against genetically modified organisms and invariably control of our economies, all because of a lack of forbearance.

Our societies are ‘now’ or ‘kagwirawo’ societies, where a short-term orientation is an everyday reality. Where the pleasure principle tends to override the survival principle. We would rather buy that nice suit or car as opposed to saving for retirement. As countries we would rather borrow and invest in a shiny airport or highway rather than ensure that the country’s children are getting a proper education. Immediate gratification carries the risk of becoming addictive and creating the impression that it is easy to be successful by living in the moment. True we need food, water, and sex in order to survive and pass our genetic code on to the next generation, but that cannot be all there is to a fulfilled life or progressive society. However the discomfort of delayed gratification and a sense of purpose seem to be things of the past. Even if he is dead, Mischel’s heirs are alive to the fact that we love our marshmallows now and they are happy to let us have them.

Samuel Sejjaaka is Country Team Leader at Mat Abacus Business School. Twitter @samuelsejjaaka